Ukraine needs to develop a network of professional science communicators: a blog by Ilona Sviezhentseva

07.11.23

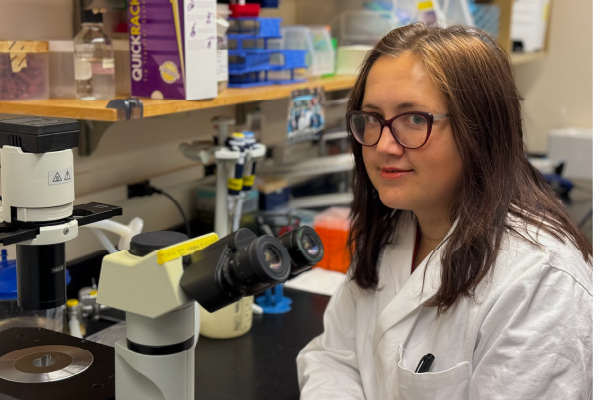

Ilona Sviezhentseva is a scientist and a science journalist. She researches biological mechanisms of leukemias that will help improve personalized treatment in the future. Ilona is currently a postdoctoral research fellow in the pediatric department of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which is a part of the network of hospitals at Harvard Medical School. At the same time, she helps communicate the subject of oncology to Ukrainian patients and their family members. Also, Ilona writes columns on science and medicine for various Ukrainian online media. In the Science at Risk project, she joined two work groups simultaneously - “Application of citizen science in times of war, crises and catastrophes” and “Science popularization during wars and crises”.

In a society that is facing hardships like wars, pandemics, or natural disasters, science often takes the back seat. People are concerned more with survival and providing for basic physiological and safety needs. The state rebuilds its apparatus including science to maximize defense capacities and renew destroyed infrastructure, and pays less attention to fields unconnected to the army, construction, or healthcare. In consequence, fundamental sciences like botany, zoology, culturology, etc. suffer.

In circumstances where expeditions are underfunded, and scientists don’t have access to occupied territories, they can engage citizens in gathering primary data to do research. At the seminars I visited at Western University (London, Canada), I talked numerous times to scientists who engage the citizens of London Ontario in their research. Moreover, the local library, in collaboration with the university, conducts Science Month every year inviting lectors - science popularizers who popularize citizen science as well. Being a Ukrainian scientist, it was in Canada that I heard about citizen science for the first time. Of course, there are citizen science projects in Ukraine as well: people actively join iNaturalist, UkrBIN, and others. Some research involving citizens was conducted in the territories occupied in 2014; however, the organizers were unaware that they used citizen science tools. They wanted to research how the occupation had affected the territory; they found volunteers and provided them secretly with instructions for data gathering. This shows that not just the average Ukrainian, but even scientists are not acquainted with the concept of citizen science.

Within the Science at Risk project, me and my colleagues researched various cases of citizen science usage all over the world, and we concluded that to engage the public in doing research, scientists and scientific institutions should speak about science systematically and make it interesting. It is the society that orders and sponsors all the research, therefore science has to be intelligeble to citizens instead of hiding in the walls of institutes and universities. Engaging the public in citizen science will help them understand the scientific process better. It is the systematic popularisation of Ukrainian science in the media and the holding of public popular science events that will make possible the involvement of volunteers in scientific projects. Moreover, this will help society understand better what Ukrainian scientists do and why their activity is crucial for the development of the state.

In Ukraine, there’s a small group of enthusiasts-popularisers ready to talk about their field of research publicly. However, they usually comment on events and phenomena in their own field of expertise, and therefore Ukrainian science is elucidated unevenly. It doesn’t mean that other scientists are unprofessional or that their research is less interesting and important. The thing is that popularisation is one of the types of public activity, a laborious process that demands additional skills, like:

— ability to explain things in plain words;

— writing non-academic texts;

— good oratorical skills.

Not all scientists have the ability to do the additional public activity, as well as not every professional has the required skills to popularize science well. That’s why it’s so important to have a network of science communicators who would have the required level of training and could explain science to the public.

To achieve this, it’s possible to use, for example, the Polish model - there started to form a grassroots network of science communicators; it all started with a group of enthusiasts at the Warsaw Copernicus museum and then spread to other voivodeships. Or we should, for instance, begin with scientific institutions and universities, where there are whole communication departments that tell about scientific discoveries of their employees for the media and lead separate sections on the websites of institutes and universities (an American model). However, Ukraine may choose a mixed version due to the circumstances, as many scientific institutions are currently damaged or occupied.

Funding for such projects and quality training for future science communicators are also important. Funding may be provided both through separate state or private grant foundations and through expenses from the budgets of scientific institutions. Successful Ukrainian science popularizers should be involved in the training for such communicators first of all. Involvement of foreign professional communicators who underwent special training will help train professionals in the fields where Ukraine lacks its own successful popularizers.